Part of the Eating with Intention Series

Principle V: Feeling Your Fullness

Imagine the last time you ate something from start to finish. Picture yourself back in that scene. You’re having a meal and you’re experiencing the action of putting food to your mouth bite by bite. Picture your pacing. Were you rushed or at ease? Alone or with others? Present or distracted? Ravenous or not hungry at all?

No matter what you ate, how you ate, or why you ate, there were two distinct moments when you started and stopped eating. The art of feeling your fullness starts with discovering what is influencing this starting and stopping process and moving us toward getting back in tune with utilizing that built-in gift of “interoceptive awareness” when eating.

Let’s look at just a few ways to imagine what comfortable fullness is. Tribole and Resch give these examples:

- A subtle feeling of stomach fullness

- Feeling satisfied and content

- Nothingness—neither hungry nor full.

If these descriptions of comfortable fullness seem unfamiliar to you, it’s likely that there have been quite a number of influences around your eating that are overriding your hunger and satiety cues. In previous articles, we’ve identified the noise and distraction of the diet mentality and the demoralization that comes from the food police (and other voices), but what else might be pushing us to disregard our hunger and satiety? The following descriptions outline some of what we might call unconscious obligations.

Tribole and Resch refer to the ever so popular “clean your plate club” which can be described as a hard-wired rule for many of us who were encouraged as children at the dinner table to not waste food by cleaning our plate at the cost of ignoring our hunger cues. Mix in a little guilt of “clean plate = you love mom/dad’s cooking = you love mom/dad” then it’s likely to grow into an ironclad habit—obligated to eat for reasons other than hunger.

Other obligations can come from habits formed from years of dieting such as, “Since I can’t eat past 7:00 pm, I should eat as much as I can now, even if I’m already full so that I don’t get hungry later.” Or, “These brownies are amazing and I really should never eat them, so I better eat as much as I can now because tomorrow I’m starting my diet.” Again we see obligatory eating, in this case, to satiate perceived deprivation. While we could go on to name several more, it goes to show that there may be many unconscious obligations for habitually eating past fullness.

It is important to note here that feeling your fullness is not a rigid rule to follow, nor is it a command expected that intuitive eaters are banned from ever overeating or over-indulging. Intuitive Eating is not a hunger and fullness diet. At the same time, if the majority of our decisions about when to start and stop eating aren’t based on interoceptive awareness of hunger and satiety, we will not be working toward the freedom with food that we hope for.

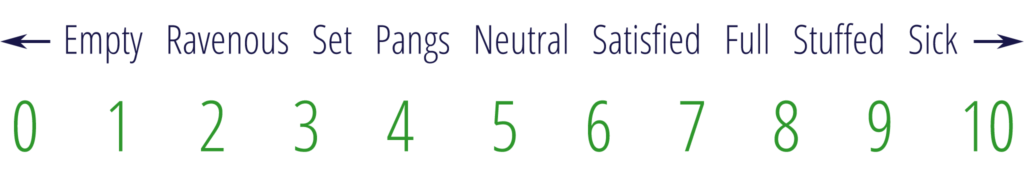

So how does one begin to key-in to hunger and satiety? One basic and valuable tool to is to start scaling our hunger. Take a look at the following Fullness Discovery Scale developed by Tribole and Resch:

Fullness Discovery Scale

In order to feel our fullness, we begin by raising our consciousness of these sensations and naming them. What’s helpful about this scale is that you can practice using it at any point during the day. With some focused tuning-in, you’ll find yourself somewhere on the scale regardless of whether you have a plate in front of you. I’d invite you to try it now as you make your way through this article.

Additionally, the Fullness Discovery Scale is more formally used at the beginning of a meal, a few minutes in, and then toward the end of a meal in the form of a simple pause—a moment to tune in and ask yourself where your fullness rates. Once you’ve established where you fall on the scale, you can begin to trust your body to be a part of the decision-making process for when you’re ready to start and stop eating. This is precisely where you’d access and apply the neutral, descriptive, non-judgmental voice of the Food Anthropologist referred to in Principle IV.

Among other variables, enhancing your ability to listen at the most basic level involves removing distractions i.e.; turning off electronics, putting your work/reading aside and intentionally stopping for that brief 20 minutes to simply eat.

If you’ve struggled with not responding to satiety and hunger for a long time, this task will take a fair amount of patience and likely a much deeper level of being present with your body than you’re used to. This might bring uncomfortable feelings. Sometimes remaining disconnected from our bodies and/or the food that we eat has become a mode of coping with discomfort in ways that we haven’t fully understood yet. If you find that slowing down in this way raises discomfort or that you simply cannot stop eating, there is a good chance that you may be using food as a coping mechanism—there will be more on this topic covered in future principles.

This is precisely where focused support from a group, a skilled and knowledgeable individual therapist or dietician can bolster self-compassion and a posture of exploration without judgment to keep moving on this healing path.

If you’re interested in learning about more principles of intuitive eating, check back for more of this weekly article series.

Source:

Tribole, E, Resch, E. Intuitive Eating. New York: St. Martins Griffin 2015. Print